Warren/Rounds Resolution Myth-Facts

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: May 20, 2022

CONTACT: Sarah Little (443) 440-0029

WASHINGTON, DC - The North American Meat Institute (Meat Institute) today released the following Myth-Fact resource debunking the mischaracterizations about beef and cattle markets in a resolution introduced by U.S. Senators Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) and Mike Rounds (R-SD):

Myth: In the press release announcing the resolution, Senator Warren says beef companies have lowered wages for workers. This assertion is completely false.

Fact: The meat and poultry industry values its workforce and, according to Rabobank and other well documented sources, average starting hourly wages for workers have increased from $14.60 to $22.00 an hour in just three years. In fact, the CEOs of Tyson and JBS recently testified before the House Agriculture Committee about workforce wages. At JBS beef facilities, average pay is nearly $24.00 an hour and starting wages are $20.00 an hour, representing a 40 percent increase since 2017. At Tyson, average compensation is $24.00 an hour or $50,000 a year. Tyson Foods testified to spending $500 million on pandemic wage increases.

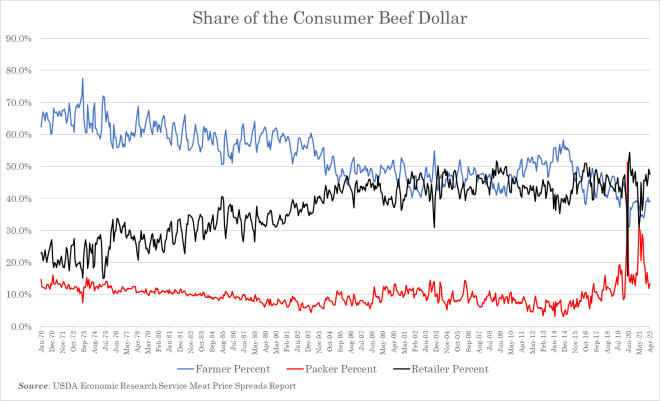

Myth : From the resolution: Whereas ranchers in the United States receive approximately 39 cents of every dollar a consumer spends on beef, compared to the 60 cents of every dollar they received 50 years ago.

Fact : The packer's share of the consumer beef dollar in April 2022 was 13.5 cents. For the 628 months beginning January 1970 through April 2022, packers have received the smallest share of the consumer beef dollar in all months but May 2020, at the peak of the COVID-related shutdowns on slaughter plants that reduced beef supplies.

Myth : From the resolution: Whereas, each year since 1980, an average of nearly 17,000 cattle ranchers have gone out of business;

Fact : Every five years, USDA's Census of Agriculture collects data on agriculture and livestock production and sales. According to the 1982 Census (the closest Census to the cited year of 1980) there were 671,702 cattle farms and ranches on which there was an end-of-the-year inventory of beef breeding cows - a necessary asset to consistently produce calves to be marketed - from which cattle and calves actually were sold. (1982 Census of Agriculture, Table 26, p 14) For context, this number includes all operations with at least one cow; in fact, 102,892 of those farms had four or fewer cows.

Losing 17,000 cattle farms and ranches per year for the 39 years since 1982 would have resulted in losing 663,000 - or 99 percent - of those farms and ranches marketing cattle in 1982. Obviously, that is not the case.

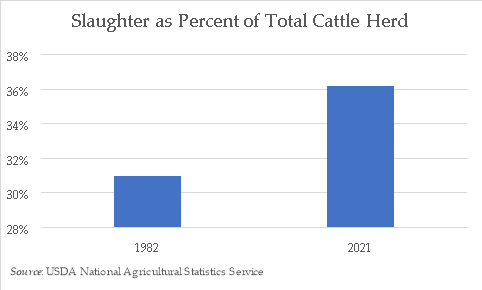

The comparison needs to be put in further context. Consider, in 1982 there were 115.4 million cattle in the U.S., and an annual slaughter of 35.8 million head that yielded 22.36 billion pounds of beef. Compare that to 2021 when U.S. beef production was a record 27.9 billion pounds, from a harvest of 33.8 million cattle out of a total herd of 93.6 million head .

In other words, packers harvest and process more cattle today compared to 40 years ago which generates greater economic benefits to farmers and ranchers. Additionally, providing more beef, to more consumers, more efficiently, tells an impressive sustainability success story for the cattle and beef industry.

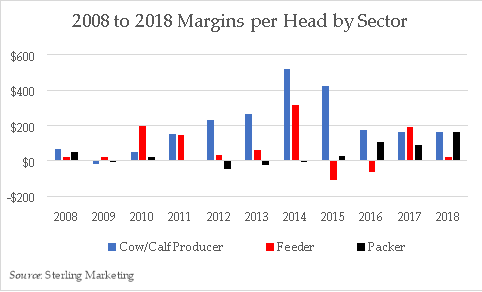

Myth : From the resolution: Whereas, between 2015 and 2018, the difference between the cost of wholesale beef and the price paid to ranchers increased by 60 percent, while the top beef packers enjoyed record profits;

Fact : Cattle prices were at record highs in 2014 and 2015 when the overall cattle herd was at its smallest since 1952 (i.e., during the Truman Administration). Those record prices incentivized rapid herd expansion among producers until the beginning-of-the-year cattle inventory in the U.S. hit its peak in January 2019. This pendulum-swing resulted in an imbalance in cattle supply and demand impacting both beef and cattle prices and further caused volatility for all sectors - cow-calf producer, feedlot, and beef packer. There are different supply and demand forces on cow-calf producers, feeders, packers, and retailers, which is why each sector can experience different market effects at the same time.

Cattle and beef markets are extremely complex. From the ranch to the slaughter plant, live cattle typically change ownership two to three times. Consider, cow/calf producers market their calves to cattle feeders, or to "backgrounders" who in turn sell those cattle to feeders. Those cattle are then sold to packers. Price at any given point in this value chain is determined by the supply of cattle to sell from one segment and the demand to buy cattle by the next segment. Then, each step in the post-slaughter process that is carried out by a variety of entities, is taken to add value and provide specific products for specific uses in various consumer markets - both retail grocery and food service, which vary significantly in product type and specifications.

To sum up this complexity, a recent paper published by the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City notes that one animal - and the beef produced from it - "could be sold as many as six times before it finally reaches the consumer." (Cowley, C. Long-Term Pressures and Prospects for the U.S. Cattle Industry, Kansas City Federal Reserve Bank Economic Review, December 17, 2021) In short, there are different supply and demand forces on cow-calf producers, feeders, packers, retailers and restaurants, which is why each sector can experience different market forces at the same time.

Cattle markets are famously cyclical. Looking back over 10 years, instead of the 3 referenced by the resolution, shows this in context.

No sector - cow-calf, feedlot, nor packer - has realized positive margins every year, however, over the cow-calf sector suffered negative margins the fewest number of years of the three as the chart above shows, and the packing sector has experienced the most.

Myth : From the resolution: Whereas the top 4 beef packers increased their market share from 32 percent to 85 percent in the past 3 decades;

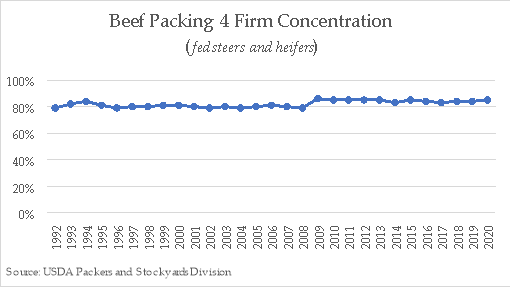

Fact : The four-firm packer concentration ratio for fed cattle slaughter has not grown more than 2.5 times over the past 30 years. Rather, beef packer concentration has not changed appreciably since 1994. According to the Agricultural Marketing Service's (AMS) Packers and Stockyards Division (P&S), the four firm concentration ratio for fed cattle was 79 percent in 1992; today it is 85 percent.

Myth : From the resolution: Whereas the top 4 beef packers control roughly 85 percent of the beef supply to the wholesale market in the United States;

Fact : Again, this is not the case, and is a misleading exaggeration. Fed cattle make up 79 percent of the total cattle slaughter. Cows and other non-fed cattle, make up the balance, primarily slaughtered to be made into hamburger. The lean meat from these animals is a necessary ingredient to be made into America's supply of hamburger produced in combination with the less demanded muscle cuts from the fed cattle. This distinction is important because up to 50 percent of all beef in the U.S. is consumed as hamburger. Even factoring in the non-fed cattle slaughter plants they own, the four largest beef packers represent about 70 percent of total U.S. beef production.

About North American Meat Institute

The Meat Institute is the United States' oldest and largest trade association representing packers and processors of beef, pork, lamb, veal, turkey, and processed meat products. NAMI members include over 350 meat packing and processing companies, the majority of which have fewer than 100 employees, and account for over 95 percent of the United States' output of meat and 70 percent of turkey production.